"Buddy Longway" was a long standing revisionist western series, published by Belgian's Le Lombard. Written and drawn by Swiss-born Derib, it provided the francophone creator with a platform to tell kinder, and more realistic frontier stories, done by purposefully ignoring the classic adventure tropes, and trying for a style that had more in common with the writings of Jack London then a typical pulp western yarn. Still, it's hard to find an European western series that was not cognizant of Charlier and Giraud's classic "Lieutenant Blueberry", if not wholly referential.

Thus, even a comic that was so calm, assured and in tune with the nature as "Buddy Longway", came to exist almost in relation to the best seller, with the art alone making it impossible not to draw comparisons. And while it could be argued that beyond the stylistic similarity the two series had little in common, Derib's brushwork seems so alike to that of pre-Moebius Giraud, that it could only have been a conscious choice on the part of the Swiss born creator to present his work using the same template.

Interestingly, the series' eight volume, "Firewater" seems to dispel any notion of Derib simply utilizing a similar style to connect to the same audience, firmly declaring himself on the page as a Giraud fan. Interestingly, this was done in such a blunt way so as to actually insert the veteran comics creator into the album as a supporting character! Thankfully, Moebius receives just a cameo role, but he is such a famous figure that calling him by name and using a very close likeness of the artist actively takes the reader out of the story to ponder the back story behind the two page gag, and the kind of relationship the two creators enjoyed at the time.

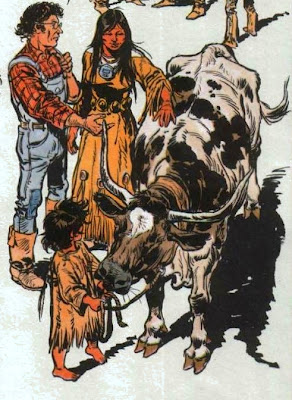

The whole scene featuring Jean Giraud, a tradesman living in an army outpost actually serves the story, and resolves a subplot involving Buddy's wife convincing the trapper to purchase some of the farm animals, so that in itself, the use of Blueberry's co-creator doesn't seem gracious beyond the obvious idea of employing such a famous likeness to illustrate a bit player. Yet, even before the cow trader is mentioned by his last name, his appearance seems particularly distinctive, even for such a realistically drawn book that features a wide variety of physical models.

Derib's style is usually a bit looser, that when it comes to Giraud's cameo appearance, just seeing a character wearing eyeglasses in such a rugged setting triggers all but the newest of Franco-Belgian albums to the in-joke. Furthermore, even the use of a French name breaks from the pattern of deliberately using English names for the cast, in order to provide a distinct American western experience.

Derib's style is usually a bit looser, that when it comes to Giraud's cameo appearance, just seeing a character wearing eyeglasses in such a rugged setting triggers all but the newest of Franco-Belgian albums to the in-joke. Furthermore, even the use of a French name breaks from the pattern of deliberately using English names for the cast, in order to provide a distinct American western experience.

By the time the reader turns the page and discovers Jean's last name (an almost unprecendented feat for the characters fulfilling that kind of a role in the story), there is no room for doubt. In his earnestness, the writer/artist somehow diminishes the poignancy of the story, but thankfully, he has chosen a reasonably lighthearted scene to subvert.

Classical Franco-Belgian albums have long been continually praised for their accessibility, as they typically stick to a successive formula that leaves room for improvisation and individuality. Even as such, books such as "Asterix the Gaul" typically play around with in jokes involving both historical figures, as well as the references to then current real life events, but "Buddy Longway" has the distinction of not being a comedy book.

Seeing caricature after caricature of Goscinny in his and Uderzo's classical series plainly works when coupled with the book's tongue in cheek humour. Yet, even Derib's closest genre comparison, "Lucky Luke" (another Goscinny co-creation) steered clear of such visibly direct homages to French comics scene. Compared to "Blueberry", the Morris pencilled cartoony western, with a complete comedic shorthand of western lifestyle is a complete antithesis to the realism of "Buddy Longway", which makes Derib's addition of Giraud even more indulgent then it seems at first glance.

Thus, even a comic that was so calm, assured and in tune with the nature as "Buddy Longway", came to exist almost in relation to the best seller, with the art alone making it impossible not to draw comparisons. And while it could be argued that beyond the stylistic similarity the two series had little in common, Derib's brushwork seems so alike to that of pre-Moebius Giraud, that it could only have been a conscious choice on the part of the Swiss born creator to present his work using the same template.

Interestingly, the series' eight volume, "Firewater" seems to dispel any notion of Derib simply utilizing a similar style to connect to the same audience, firmly declaring himself on the page as a Giraud fan. Interestingly, this was done in such a blunt way so as to actually insert the veteran comics creator into the album as a supporting character! Thankfully, Moebius receives just a cameo role, but he is such a famous figure that calling him by name and using a very close likeness of the artist actively takes the reader out of the story to ponder the back story behind the two page gag, and the kind of relationship the two creators enjoyed at the time.

The whole scene featuring Jean Giraud, a tradesman living in an army outpost actually serves the story, and resolves a subplot involving Buddy's wife convincing the trapper to purchase some of the farm animals, so that in itself, the use of Blueberry's co-creator doesn't seem gracious beyond the obvious idea of employing such a famous likeness to illustrate a bit player. Yet, even before the cow trader is mentioned by his last name, his appearance seems particularly distinctive, even for such a realistically drawn book that features a wide variety of physical models.

Derib's style is usually a bit looser, that when it comes to Giraud's cameo appearance, just seeing a character wearing eyeglasses in such a rugged setting triggers all but the newest of Franco-Belgian albums to the in-joke. Furthermore, even the use of a French name breaks from the pattern of deliberately using English names for the cast, in order to provide a distinct American western experience.

Derib's style is usually a bit looser, that when it comes to Giraud's cameo appearance, just seeing a character wearing eyeglasses in such a rugged setting triggers all but the newest of Franco-Belgian albums to the in-joke. Furthermore, even the use of a French name breaks from the pattern of deliberately using English names for the cast, in order to provide a distinct American western experience.By the time the reader turns the page and discovers Jean's last name (an almost unprecendented feat for the characters fulfilling that kind of a role in the story), there is no room for doubt. In his earnestness, the writer/artist somehow diminishes the poignancy of the story, but thankfully, he has chosen a reasonably lighthearted scene to subvert.

Classical Franco-Belgian albums have long been continually praised for their accessibility, as they typically stick to a successive formula that leaves room for improvisation and individuality. Even as such, books such as "Asterix the Gaul" typically play around with in jokes involving both historical figures, as well as the references to then current real life events, but "Buddy Longway" has the distinction of not being a comedy book.

Seeing caricature after caricature of Goscinny in his and Uderzo's classical series plainly works when coupled with the book's tongue in cheek humour. Yet, even Derib's closest genre comparison, "Lucky Luke" (another Goscinny co-creation) steered clear of such visibly direct homages to French comics scene. Compared to "Blueberry", the Morris pencilled cartoony western, with a complete comedic shorthand of western lifestyle is a complete antithesis to the realism of "Buddy Longway", which makes Derib's addition of Giraud even more indulgent then it seems at first glance.

What is the most problematic with Swiss born author's decision is simply that it has no place in what is otherwise a very mature presentation. There are plenty of other comics, both primarily for younger readers and those that are not, that continue the medium's long tradition of using gimmicks and in jokes to create a playful sense of community which enables the readers to connect with the creator's vision and political commentary. "Buddy Longway", with it's archetypal stories of understatement, the struggle and coexistence between the man and the nature, the basic naivety and kindheartedness of it's protagonist, all seem resistant to such practice.

Derib must have felt so obliged to his creative predecessor that he deemed it fitting to formalize the connection on page, but the story involving the odd behaviour of young Native Americans causing distress in nature and the population of the region seems a wrong place to place his homage in. No doubt Charlier and Giraud's stories, many of them starring very sympathetic version of Indians, must have served as a direct inspiration for this, and no doubt several of the earlier entries in Derib's series, but perhaps an another two page sequence disconnected from the standard narrative would have illustrated the point much more directly, without trying to wink at what must have been an overlapping audience between the two titles.

No comments:

Post a Comment