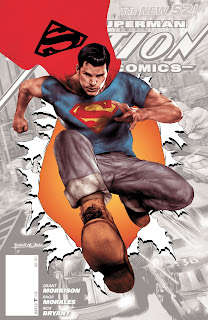

ACTION COMICS #0

Grant Morrison's "Action Comics" run started very early in the career of the first and most famous superhero, making the company's prerequisite #0 prequel issue largely superfluous. Both Clark's origins and his early days have been the topic of countless retellings, but this issue purports to reveal the exact circumstances behind his origin in "New 52".

Penciller/inker Ben ("Vigilante") Oliver for the moment replaces Rags Morales as the artist behind the T-shirt and jeans Superman's debut. His work here is somber and figure oriented, serving to ground the fantastic events in the sepia toned uneasiness. It works to instill a sense of past the recent past, but it still imbues the story with a wearisome tone, that works better with the subplot involving the titular "Boy who stole Superman's cape".

Morrison chooses an early transitory period in Clark's life in Metropolis, and frames the story around the question of how he ended up with the Superman moniker. The writer uses a couple of pages showing the protagonist settling in to his new apartment to set up the forthcoming arc starring Mr. Mxyzptlk, but he mostly focuses on the regular supporting cast. It's Clark's colleagues in the rival Daily Planet that get to asks the questions regarding his cape and the nature of his powers.

Typically, this kind of story doesn't really challenge Morrison's sensibilities as the writer. The departing scribe tries for his professional best, but it's hard to exhibit much enthusiasm when tackling material this well tread. As for the Luke, the child that steals the cape to confront an abusive father figure, his story is about as perfunctory as the rest of the issue. It serves to both encapsulate the wish fulfillment behind the Superman's powers, as well as to remind the reader of his role as the champion of the oppressed.

Yet, the regular reader of the title is deeply aware how quickly Morrison dismisses with the more grounded elements of Superman's accomplishments. The issue even climaxes with the scene featuring Clark stopping a train, a clear callback to his actions in Morrison's first issue. It's not to say that there's no style on display here, but there is a definite sense that the company is forcing the writer to repeat himself very soon after debuting with what is essentially the same story. It is unfortunate that the company did not simply reschedule the story as an Annual, and have commissioned a script from one of their other freelancers.

Of course, this is exactly what the company is already doing with the back-up. This time, Sholly Fisch returns with a simply story detailing the origins of Captain Comet. The writer's script is very accessible and more traditional, as is CAFU's art. The reader follows a scientist researching the truth behind the Blake Farm ghost story, who ends up meeting Adam at a crucial point, which forever alters his life. The short ends with a hint linking the events to the Andy Kubert pencilled fill-in arc from issues #5 and 6, but it reads just as well for the reader who is unaware of the connection.

BOYS #70

With the series set to conclude with #72, the biggest impression this issue makes is how calm it appears. There is no sign of rushing through the plot lines, character behavior that feels sudden and off key, and a general sense of the creators losing control of the series, unable to properly finish their work. If anything, Ennis and Braun treat this issue like any other in the series, quickly setting the somber mood and following the rising tension until the cliffhanger.

The spotlight is kept firmly on Wee Hughie, and his fragile state of mind, as the character tries to cope with last issue's cliffhanger. Throughout "the Boys", Hughie has been the reader identification figure, a flawed and sensitive young man, whose presence has managed to ground the series in the best way.

Throughout the series, the Scotsman has been surrounded by veterans of the decades of superhero conspiracy, who exhibited a great deal of patience regarding his many misgivings. At this point in the series he has been left without their help, and for once there is no one around to shoulder his pain. Realizing this, Hughie goes about his way, encountering two of the series' odder mysteries.

It should be noted that both of these are of a nature that would have made it extremely unlikely that would have passed the original publisher DC/Wildstorm's consent. The first of these is quickly wrapped up, but there is a sense that the writer is deliberately focusing of the body horror aspect of the scene, to distract from what it could signify story wise.

Russ Braun's artwork likewise skirts the line of horror and parody, with his design of the "monster" in the basement going completely over the top. The Vought-American subplot gets its requisite three pages, this time a lovely choreographed dialogue scene that finally starts addressing the obvious question of the choice of the scapegoat for the company's failings.

The slowly escalating plot allows for one final diversion before the finishing set piece, dealing with another minor series' mystery. This time, Ennis uses the opportunity to directly tie it into Wee Hughie's forthcoming confrontation with the Butcher. Faced with even more evidence of his tutor's shady dealings, the writer lets the protagonist gathers his thoughts, before heading off to finally meet him face to face.

A particular coloring choice carried out through the issue becomes more than apparent in this sequence, as the texture used to indicate Hughie being covered in soot somewhat distracts from the more traditional colors otherwise employed. The use of water colors (or more likely, a computer filter fulfilling the same purpose) feels somewhat distracting when placed over Braun's rendering of Hughie, even though it adds to the feeling of the hopelessness emitted by the character who faced with overwhelming odds.

The episode ends with the sequence featuring another New York landmark, which has added resonance following last issue's end. The slow burning conflict feels natural, with Ennis' dialogue perfectly pitched and life like. Braun's frames the sequence in a way that competently dramatizes the deeper conflict, which breaks only for the cliffhanger.

In the end, the readers get to benefit for having two more issues of the series to look forward too. Each of the plot lines has been given a proper send off so far, and barring any last minute rushing, the eventual fate of Vought-American superhuman handler, Annie, Hughie and Butcher, is likely to be a culmination of everything that's lead up to this point, in the best possible way. It's extremely rare for a series to be executing its final arc this well and "the Bloody doors off" is at this point setting up to be the title's best arc.

HAWKEYE #2

Having established his take on the character last issue, Matt Fraction and David Aja use the second entry in the series to set up their story. In essence, the creative team seems to be using the backdrop of global depression to tell the adventures of Clint Burton as a modern day Robin Hood, while still working in the milieu of Marvel universe.

Starting with this issue, the book includes Young Avengers' Kate Bishop, the teenager that used the Hawkeye moniker as a spunky sidekick. Matt Hollingsworth provides a palette of differing shades of purple, the color traditionally associated with the Avenger, helping the creative team realize their stylish superhero book.

In trying to maximize the effectiveness of the artist's detailed, intuitive panels, Fraction deliberately slows down pacing with a combination of naturalistic narration and quirky dialogue. In effect, this frequently breaks down Aja's pages into a high number of panels, trying to capture the details of the mood and atmosphere, imbuing the book with another layer of personality.

At this point, the book lacks the sense of fluidity that characterized Waid and Rivera's "Daredevil", the book's closest match when it comes to the publisher's output. Both of the creators seems to be trying hard to make the experience special both for them and the reader, in the process creating a comic that tries to be too many things at once.

On one level, "Hawkeye" wants to be a slick heist story in the vein of James Bond. Unfortunately, the addition of Marvel supervillains serves to remind the reader that they are reading a variation on a superhero formula that can only go so much before circling back to the same tropes. For the moment, the writer may be concentrating on Hawkeye's circus past and not on his more traditional days, but it's only a couple of pages later that the he brings in the Swordsman connection.

In trying to honor the essence of the character, Fraction is well aware that he has to include Hawkeye as a superhero, but he tries to keep his archery skills in the background, making it all the more special when the character finally uses them in action. Even then, the protagonists helpfully point out that they are using nonlethal violence, another hallmark of the limitations placed on the superhero storytelling.

There is no doubt that both of these accomplished creators have a plan with "Hawkeye", and it may be that in time they'll manage to build upon the foundation laid here, but at the moment the book feels labored and less than the sum of its parts.

MIGHTY THOR #19

"Everything burns" continues in "Thor", with Alan Davis returning to pencil this part of the crossover. Once again, the writers reiterate the information pertinent to the new Aesir/Vanir war, maintaining the tone of the event focused on character conflict. It's telling that a two page sequence tries to inform the reader that this is the conflict raging in huge battles all over the Nine Realms, but in practice it feels like nothing as such.

Until now, the war has consisted of an opening barrage and is more or less still in the opening stages of the conflict. Mainly, Thor and his friends are still debating the way to deal with the Surtur-powered threat, with the creators adding in the aforementioned sequence precisely for the purpose of fulfilling genre expectations.

This is not to say that "the Mighty Thor" features no fight sequences. The issue starts by picking up on the cliffhanger from "Journey into Mystery", featuring a fight between Thor and the Warriors Three. It is is a familiar image, if not the most welcome one, but Fandrall's subsequent derision works to make it a bit more authentic than the average clash between heroes.

These characters have traditionally be prone to speechifying, but their actions so far feel somewhat out of character. Seeing Thor address the Loki by putting the child in the choke-hold further undermines the strange state of the series the event is spinning out of. With Freya's characterization, Fraction and Gillen have finally managed to get some storytelling opportunity from the character's raised profile, but the wider trinity of Allmothers still feels strange and out of touch.

Idunn and Gaea‘s role never managed to stretch beyond the symbolism, with Odin continuing to play a larger role even though he is absent from the proceedings. The issue finishes up on a promising cliffhanger that further integrates how personal the conflict feels to both Thor and (especially) Loki.

All things considered, despite the creators' best efforts, the crossover is unlikely to prove relevant beyond the current moment in both "the Mighty Thor" and "Journey into Mystery", but the story certainly feels larger and more important than anything following "Fear Itself". And while "Everything burns" lacks the more universal appeal of the wider Marvel universe crossover, it more than makes up in its tone that is respectful to both the Lee/Kirby interpretation of the Norse mythology, as well as everything that Fraction and Gillen brought to their respective titles.

PUNISHER #15

The penultimate issue of the Rucka/Chechetto run on "the Punisher" (before the title transforms into the "War Zone" mini-series that will wrap up this take on the character) deals with the fallout of Frank and Rachel's last issue's mission. After last issue's flawless showdown with the Exchange, the vigilantes are forced to contend with one last bit of unfinished business.

The things quickly spin out of control, as one loose end overreacts to the shootout, leading the Exchange leader to maniacal lengths. As always, it goes without saying that Rucka's script works as a story in its own right, providing everything the reader needs to understand the events in motion, without resorting to expository monologues.

The creators are depicting an ugly situation, but the approach their utilizing is anything but. The bulk of the realization falls on the hands of Chechetto, with the returning penciller/inker realizing all of the disturbing events in the way that is both concise and powerful. The reader is at all times aware where each of the characters are in opposition to one other, except for the very end, where the lack of perspective becomes an important story point.

Marco Chechetto's return to these pages after two fill-in issues feels very welcome, as his powerful, animated figures have come to define this approach. The artist naturally feels much more at home with the character designs than Mico Suayan, even though he lacks the latter's darker edge. The brighter colors do somehow re-frame the horrible massacre into something approaching video game violence, but for better or worse, this was the way the title has always worked in the hands of these two creators.

The crux of the issue revolves around Frank's tactical approach in a situation going haywire, which ends with a seeming demise of a cast member. The antagonist willingly sacrifices himself to bring Frank and Rachel in conflict with the authorities, providing the impetus for stories now that two have dealt away with the Exchange organization.

At this point, it's pure speculation whether Rucka's original series overview included provided for the inclusion of superheroes that will have large roles in the "War Zone" mini-series. The conclusion of this issue certainly hints at an extended hostility with the local authorities, but the creative team's insistence that their story takes place in the superhero universe certainly provides for a possibility of a larger role for the superhuman community.

VENOM #24

The greatest compliment that could be given to Cullen Bunn's second issue as a solo writer of "Venom" is that the story stars to read as a comic in its own right. Even though it recasts Daimon Hellstorm as a generic sadistic monster, and has very little to do with Venom or Flash Thompson, "Monsters of Evil" is at least starting to function as an entity of it own.

The story legitimizes itself as the follow-up of the "Circle of Four" crossover, which only complicates the matters. In order to get to the pulp thrills that Bunn is trying to carry over, the writer has to meander through both the internal logistics of Marvel universe and the series' own continuity. At this point, the reader is made to feel every leaden step of his way through both of these, resulting in an overloaded synopsis.

Flash Thompson is the man who has had the Venom symbiote grafted to him, whose soul has been marked by Blackthorn the devil as part of the story in which he met Hellstrom. Following up on a McGuffin, Venom ends up being duped by Hellstorm, who possesses the symbiote with a demon. Having discovered that he still has a measure of control due to the mark on his soul, Flash tries to get the demon out of his body, first by visiting a local exorcist, before confronting Hellstorm and trying to force Daimon to restore him to his previous condition.

It's a needlessly convoluted set-up, that substitutes the title's inherent possession analogy with a literal demonic possession, in order to tell the story the writer is interested in. Bunn is purposefully distancing the title from its roots as a Spider-Man spin-off, which again makes the story all the more generic and unnecessary. The reader is to forget that he is reading about Flash Thompson, and instead try to embrace the new supporting characters lacking both the charisma and the sense of family of the original Spider-Man supporting cast.

In many ways, Bunn's story is struggling with both the format and the title it's appearing in, and Tony Silas does little to provide the individualization the writer strives so hard for. The penciller exhibits solid designing skills when it comes to the exorcist and the titular Monsters of Evil, that appear on the ending double page spread. Otherwise, his linework is neither caricatural enough to compare to the opening Tony Moore issues, nor does he exhibit a strong sense of naturalistic draftsmanship that Lan Medina had in his issues of the title.

Silas' Venom seems credible enough when in the traditional Agent Venom mode, but he fails to find a way to make the demonic transformations work in a consistent way. The images are gross but random, without the full demon-Venom form appearing particularly uninspired. Yet, despite the lack of embellishment, Silas' layouts maintain a clarity that helps his inherently dramatic art carry the story.

It's a shame that Bunn wasn't allowed to start a brand new volume of "Venom" stories on his own, as "Monsters of Evil" would have certainly read more organically had he been allowed to set the story up on his own. This way, in light of Rick Remender's scripts, Bunn's more traditional genre adventure work lacks the personal touch Rick Remender had managed to graft onto the grim an gritty villain fused with the body of a longtime Spider-Man supporting character.

Grant Morrison's "Action Comics" run started very early in the career of the first and most famous superhero, making the company's prerequisite #0 prequel issue largely superfluous. Both Clark's origins and his early days have been the topic of countless retellings, but this issue purports to reveal the exact circumstances behind his origin in "New 52".

Penciller/inker Ben ("Vigilante") Oliver for the moment replaces Rags Morales as the artist behind the T-shirt and jeans Superman's debut. His work here is somber and figure oriented, serving to ground the fantastic events in the sepia toned uneasiness. It works to instill a sense of past the recent past, but it still imbues the story with a wearisome tone, that works better with the subplot involving the titular "Boy who stole Superman's cape".

Morrison chooses an early transitory period in Clark's life in Metropolis, and frames the story around the question of how he ended up with the Superman moniker. The writer uses a couple of pages showing the protagonist settling in to his new apartment to set up the forthcoming arc starring Mr. Mxyzptlk, but he mostly focuses on the regular supporting cast. It's Clark's colleagues in the rival Daily Planet that get to asks the questions regarding his cape and the nature of his powers.

Typically, this kind of story doesn't really challenge Morrison's sensibilities as the writer. The departing scribe tries for his professional best, but it's hard to exhibit much enthusiasm when tackling material this well tread. As for the Luke, the child that steals the cape to confront an abusive father figure, his story is about as perfunctory as the rest of the issue. It serves to both encapsulate the wish fulfillment behind the Superman's powers, as well as to remind the reader of his role as the champion of the oppressed.

Yet, the regular reader of the title is deeply aware how quickly Morrison dismisses with the more grounded elements of Superman's accomplishments. The issue even climaxes with the scene featuring Clark stopping a train, a clear callback to his actions in Morrison's first issue. It's not to say that there's no style on display here, but there is a definite sense that the company is forcing the writer to repeat himself very soon after debuting with what is essentially the same story. It is unfortunate that the company did not simply reschedule the story as an Annual, and have commissioned a script from one of their other freelancers.

Of course, this is exactly what the company is already doing with the back-up. This time, Sholly Fisch returns with a simply story detailing the origins of Captain Comet. The writer's script is very accessible and more traditional, as is CAFU's art. The reader follows a scientist researching the truth behind the Blake Farm ghost story, who ends up meeting Adam at a crucial point, which forever alters his life. The short ends with a hint linking the events to the Andy Kubert pencilled fill-in arc from issues #5 and 6, but it reads just as well for the reader who is unaware of the connection.

BOYS #70

With the series set to conclude with #72, the biggest impression this issue makes is how calm it appears. There is no sign of rushing through the plot lines, character behavior that feels sudden and off key, and a general sense of the creators losing control of the series, unable to properly finish their work. If anything, Ennis and Braun treat this issue like any other in the series, quickly setting the somber mood and following the rising tension until the cliffhanger.

The spotlight is kept firmly on Wee Hughie, and his fragile state of mind, as the character tries to cope with last issue's cliffhanger. Throughout "the Boys", Hughie has been the reader identification figure, a flawed and sensitive young man, whose presence has managed to ground the series in the best way.

Throughout the series, the Scotsman has been surrounded by veterans of the decades of superhero conspiracy, who exhibited a great deal of patience regarding his many misgivings. At this point in the series he has been left without their help, and for once there is no one around to shoulder his pain. Realizing this, Hughie goes about his way, encountering two of the series' odder mysteries.

It should be noted that both of these are of a nature that would have made it extremely unlikely that would have passed the original publisher DC/Wildstorm's consent. The first of these is quickly wrapped up, but there is a sense that the writer is deliberately focusing of the body horror aspect of the scene, to distract from what it could signify story wise.

Russ Braun's artwork likewise skirts the line of horror and parody, with his design of the "monster" in the basement going completely over the top. The Vought-American subplot gets its requisite three pages, this time a lovely choreographed dialogue scene that finally starts addressing the obvious question of the choice of the scapegoat for the company's failings.

The slowly escalating plot allows for one final diversion before the finishing set piece, dealing with another minor series' mystery. This time, Ennis uses the opportunity to directly tie it into Wee Hughie's forthcoming confrontation with the Butcher. Faced with even more evidence of his tutor's shady dealings, the writer lets the protagonist gathers his thoughts, before heading off to finally meet him face to face.

A particular coloring choice carried out through the issue becomes more than apparent in this sequence, as the texture used to indicate Hughie being covered in soot somewhat distracts from the more traditional colors otherwise employed. The use of water colors (or more likely, a computer filter fulfilling the same purpose) feels somewhat distracting when placed over Braun's rendering of Hughie, even though it adds to the feeling of the hopelessness emitted by the character who faced with overwhelming odds.

The episode ends with the sequence featuring another New York landmark, which has added resonance following last issue's end. The slow burning conflict feels natural, with Ennis' dialogue perfectly pitched and life like. Braun's frames the sequence in a way that competently dramatizes the deeper conflict, which breaks only for the cliffhanger.

In the end, the readers get to benefit for having two more issues of the series to look forward too. Each of the plot lines has been given a proper send off so far, and barring any last minute rushing, the eventual fate of Vought-American superhuman handler, Annie, Hughie and Butcher, is likely to be a culmination of everything that's lead up to this point, in the best possible way. It's extremely rare for a series to be executing its final arc this well and "the Bloody doors off" is at this point setting up to be the title's best arc.

HAWKEYE #2

Having established his take on the character last issue, Matt Fraction and David Aja use the second entry in the series to set up their story. In essence, the creative team seems to be using the backdrop of global depression to tell the adventures of Clint Burton as a modern day Robin Hood, while still working in the milieu of Marvel universe.

Starting with this issue, the book includes Young Avengers' Kate Bishop, the teenager that used the Hawkeye moniker as a spunky sidekick. Matt Hollingsworth provides a palette of differing shades of purple, the color traditionally associated with the Avenger, helping the creative team realize their stylish superhero book.

In trying to maximize the effectiveness of the artist's detailed, intuitive panels, Fraction deliberately slows down pacing with a combination of naturalistic narration and quirky dialogue. In effect, this frequently breaks down Aja's pages into a high number of panels, trying to capture the details of the mood and atmosphere, imbuing the book with another layer of personality.

At this point, the book lacks the sense of fluidity that characterized Waid and Rivera's "Daredevil", the book's closest match when it comes to the publisher's output. Both of the creators seems to be trying hard to make the experience special both for them and the reader, in the process creating a comic that tries to be too many things at once.

On one level, "Hawkeye" wants to be a slick heist story in the vein of James Bond. Unfortunately, the addition of Marvel supervillains serves to remind the reader that they are reading a variation on a superhero formula that can only go so much before circling back to the same tropes. For the moment, the writer may be concentrating on Hawkeye's circus past and not on his more traditional days, but it's only a couple of pages later that the he brings in the Swordsman connection.

In trying to honor the essence of the character, Fraction is well aware that he has to include Hawkeye as a superhero, but he tries to keep his archery skills in the background, making it all the more special when the character finally uses them in action. Even then, the protagonists helpfully point out that they are using nonlethal violence, another hallmark of the limitations placed on the superhero storytelling.

There is no doubt that both of these accomplished creators have a plan with "Hawkeye", and it may be that in time they'll manage to build upon the foundation laid here, but at the moment the book feels labored and less than the sum of its parts.

MIGHTY THOR #19

"Everything burns" continues in "Thor", with Alan Davis returning to pencil this part of the crossover. Once again, the writers reiterate the information pertinent to the new Aesir/Vanir war, maintaining the tone of the event focused on character conflict. It's telling that a two page sequence tries to inform the reader that this is the conflict raging in huge battles all over the Nine Realms, but in practice it feels like nothing as such.

Until now, the war has consisted of an opening barrage and is more or less still in the opening stages of the conflict. Mainly, Thor and his friends are still debating the way to deal with the Surtur-powered threat, with the creators adding in the aforementioned sequence precisely for the purpose of fulfilling genre expectations.

This is not to say that "the Mighty Thor" features no fight sequences. The issue starts by picking up on the cliffhanger from "Journey into Mystery", featuring a fight between Thor and the Warriors Three. It is is a familiar image, if not the most welcome one, but Fandrall's subsequent derision works to make it a bit more authentic than the average clash between heroes.

These characters have traditionally be prone to speechifying, but their actions so far feel somewhat out of character. Seeing Thor address the Loki by putting the child in the choke-hold further undermines the strange state of the series the event is spinning out of. With Freya's characterization, Fraction and Gillen have finally managed to get some storytelling opportunity from the character's raised profile, but the wider trinity of Allmothers still feels strange and out of touch.

Idunn and Gaea‘s role never managed to stretch beyond the symbolism, with Odin continuing to play a larger role even though he is absent from the proceedings. The issue finishes up on a promising cliffhanger that further integrates how personal the conflict feels to both Thor and (especially) Loki.

All things considered, despite the creators' best efforts, the crossover is unlikely to prove relevant beyond the current moment in both "the Mighty Thor" and "Journey into Mystery", but the story certainly feels larger and more important than anything following "Fear Itself". And while "Everything burns" lacks the more universal appeal of the wider Marvel universe crossover, it more than makes up in its tone that is respectful to both the Lee/Kirby interpretation of the Norse mythology, as well as everything that Fraction and Gillen brought to their respective titles.

PUNISHER #15

The penultimate issue of the Rucka/Chechetto run on "the Punisher" (before the title transforms into the "War Zone" mini-series that will wrap up this take on the character) deals with the fallout of Frank and Rachel's last issue's mission. After last issue's flawless showdown with the Exchange, the vigilantes are forced to contend with one last bit of unfinished business.

The things quickly spin out of control, as one loose end overreacts to the shootout, leading the Exchange leader to maniacal lengths. As always, it goes without saying that Rucka's script works as a story in its own right, providing everything the reader needs to understand the events in motion, without resorting to expository monologues.

The creators are depicting an ugly situation, but the approach their utilizing is anything but. The bulk of the realization falls on the hands of Chechetto, with the returning penciller/inker realizing all of the disturbing events in the way that is both concise and powerful. The reader is at all times aware where each of the characters are in opposition to one other, except for the very end, where the lack of perspective becomes an important story point.

Marco Chechetto's return to these pages after two fill-in issues feels very welcome, as his powerful, animated figures have come to define this approach. The artist naturally feels much more at home with the character designs than Mico Suayan, even though he lacks the latter's darker edge. The brighter colors do somehow re-frame the horrible massacre into something approaching video game violence, but for better or worse, this was the way the title has always worked in the hands of these two creators.

The crux of the issue revolves around Frank's tactical approach in a situation going haywire, which ends with a seeming demise of a cast member. The antagonist willingly sacrifices himself to bring Frank and Rachel in conflict with the authorities, providing the impetus for stories now that two have dealt away with the Exchange organization.

At this point, it's pure speculation whether Rucka's original series overview included provided for the inclusion of superheroes that will have large roles in the "War Zone" mini-series. The conclusion of this issue certainly hints at an extended hostility with the local authorities, but the creative team's insistence that their story takes place in the superhero universe certainly provides for a possibility of a larger role for the superhuman community.

VENOM #24

The greatest compliment that could be given to Cullen Bunn's second issue as a solo writer of "Venom" is that the story stars to read as a comic in its own right. Even though it recasts Daimon Hellstorm as a generic sadistic monster, and has very little to do with Venom or Flash Thompson, "Monsters of Evil" is at least starting to function as an entity of it own.

The story legitimizes itself as the follow-up of the "Circle of Four" crossover, which only complicates the matters. In order to get to the pulp thrills that Bunn is trying to carry over, the writer has to meander through both the internal logistics of Marvel universe and the series' own continuity. At this point, the reader is made to feel every leaden step of his way through both of these, resulting in an overloaded synopsis.

Flash Thompson is the man who has had the Venom symbiote grafted to him, whose soul has been marked by Blackthorn the devil as part of the story in which he met Hellstrom. Following up on a McGuffin, Venom ends up being duped by Hellstorm, who possesses the symbiote with a demon. Having discovered that he still has a measure of control due to the mark on his soul, Flash tries to get the demon out of his body, first by visiting a local exorcist, before confronting Hellstorm and trying to force Daimon to restore him to his previous condition.

It's a needlessly convoluted set-up, that substitutes the title's inherent possession analogy with a literal demonic possession, in order to tell the story the writer is interested in. Bunn is purposefully distancing the title from its roots as a Spider-Man spin-off, which again makes the story all the more generic and unnecessary. The reader is to forget that he is reading about Flash Thompson, and instead try to embrace the new supporting characters lacking both the charisma and the sense of family of the original Spider-Man supporting cast.

In many ways, Bunn's story is struggling with both the format and the title it's appearing in, and Tony Silas does little to provide the individualization the writer strives so hard for. The penciller exhibits solid designing skills when it comes to the exorcist and the titular Monsters of Evil, that appear on the ending double page spread. Otherwise, his linework is neither caricatural enough to compare to the opening Tony Moore issues, nor does he exhibit a strong sense of naturalistic draftsmanship that Lan Medina had in his issues of the title.

Silas' Venom seems credible enough when in the traditional Agent Venom mode, but he fails to find a way to make the demonic transformations work in a consistent way. The images are gross but random, without the full demon-Venom form appearing particularly uninspired. Yet, despite the lack of embellishment, Silas' layouts maintain a clarity that helps his inherently dramatic art carry the story.

It's a shame that Bunn wasn't allowed to start a brand new volume of "Venom" stories on his own, as "Monsters of Evil" would have certainly read more organically had he been allowed to set the story up on his own. This way, in light of Rick Remender's scripts, Bunn's more traditional genre adventure work lacks the personal touch Rick Remender had managed to graft onto the grim an gritty villain fused with the body of a longtime Spider-Man supporting character.

No comments:

Post a Comment